|

|

Two Vicars for the Casserole

Following are the first six chapters of Anrew Montgomery's autobiographical novel Two Vicars for the Casserole. The paperback, which can be purchased at Lulu, comes highly recommended. Illustrations by Ash Latham.

CHAPTER ONE: ALDERNEY

The Channel Islands, those three words conjuring up sunshine, palm trees, white sandy beaches, tax-free drinks and cigarettes. Gatwick Airport was quiet, and our flight was called, on time. A smart and efficient-looking air hostess, with clipboard, forage cap and smile fixed firmly in place, led us out to the ’plane. My spirits sank when I saw it - a tiny, four-engined Heron which could take sixteen. “At least,” I cheered myself up by thinking, “we’ll get free gin but there’s not much room to get a trolley down the aisle”, as I climbed the three short steps and poked my head around the door.

“I wonder how she is going to get the trolley over that?” – ‘that’ being an enormous hump which crossed the narrow aisle - the main spar holding the wings on.

“Enjoy your flight”, the hostess smiled, then slammed the door shut from the outside. “Ah well, fasten safety belts.” Soon we were aloft in clear, sunny skies, and after about half an hour I looked down and saw a tiny island which looked most inviting and friendly, with small coves and sandy beaches, with the centre rising steeply, seemingly mostly grass-covered. “Must be Herm”, I thought, knowing my Channel Island names, but being sadly lacking in geographical knowledge. “We’ll soon be in Alderney.” We came in closer and closer, a long breakwater became visible, then a harbour, a church, houses and boats looking as though they were floating on air, the turquoise water was so still and clear.

“We’re not going to try and land this on that, there isn’t room!” But on we flew, inexorably, and lower and lower, until we were level with the top of a vertical cliff, flew up a steep valley, and plopped neatly down on a well-cropped grass airstrip, and rumbled to a clattering halt. Once the engines were cut, the quietness was almost oppressive.

Mum and Dad were there to meet me, with an ancient but dignified, faded pale blue half-timbered Morris Minor Traveller. Down from the airfield, through the cobbled streets of the small town, down towards the harbour and Braye Bay.

The house was in a cheerful, narrowing bit of street between the school and the Harbour Lights Hotel. A black dog, sound asleep in the middle of the road, woke, and ambled out of our way. Two tow-headed children, serious, hand in hand, in bathers, one of them holding a bucket, the other a shrimping net, picked their way between cottages, heading for the golden sweep of Braye. (continues after the jump...)

The house’s accommodation had been duplicated both up and down, so that self-catering families could rent the ground floor, have their own front door, and access to the flower-laden yard, while Mum and Dad used the top two storeys, and had their own entrance. Left alone to unpack and freshen up, I heard Mum call up the stairs; “We’re going camping - leaving in ten minutes!” “Oh no!” I thought, “Not camping again!” - a lot of my holidays having been spent under canvas. “What are they on about?”

Mum and Dad met while on an archaeological dig at Drax in Yorkshire, and so being in a tent was second nature to them both, but why oh why go camping when you have a perfectly good house, and a nice, warm, dry bed to sleep in? Besides, I was here on holiday.

Getting downstairs, I said, “Camping, where?”

“In the High Street.”

“Yes, certainly - in a back garden?”

“Don't be daft - come on, we'll show you.”

What the hell are they talking about? This kind of cross-purpose conversation always makes me tired and my mind go numb. Getting into the car I noticed a complete absence of camping gear, so I kept quiet.

Dad slowed the car in the High Street unlike any ‘High Street’ I had ever seen. Pink, white, yellow, blue-washed cottages, a cobbled road, uneven pavement, and a total lack of cars apart from our own. No WH Smith, Boots, BHS in sight. Only a couple of wandering holiday-makers who were craning their necks looking at some unusual feature of some gable or sash. Plus a pub, with its sign showing a sailing vessel, with, underneath, the title ‘The Campania’. Daylight at last!

Blinking in the gloom after the brightness of the street, I was bought a drink, and shown the mural of Braye Bay, now fast disappearing under years of tobacco smoke.

The Hammonds were the owners, and judging by the crowded popularity of the lunchtime session, it was a well-patronised pub. I got that castaway, beachcomber sort of feeling that told you you didn’t have to do anything if you didn't want to, or do anything in any particular order, in any special way, or at any set time.

Several lazy days passed. I borrowed the car sometimes, at others I walked, exploring the beaches, caves and bays, with their evocative names - Saye, Telegraph, Clonque, Platte Saline, Arch, Cats, Corblets, and the mostly derelict Victorian forts, some reinforced by the Germans when they occupied the all but evacuated island in 1940.

Brigg’s Hotel was a fair size for the Island, and I got to know the owners, and John, who was looking after the food and rooms. Being by now short of holiday cash, and being prompted to action by his asking if I had any waiting-on experience, knowing I was in the trade, I said I had, and when I was offered a job, promptly took it. Start tomorrow, 8.00 am.

I was lent the requisite black trousers and bow-tie, and making my way to the kitchen, met Alistair, a fairly tall, thin, dark-haired Glaswegian, who was the only other waiter. I was shown the ropes, and soon found my way about. Amongst our guests was a typical ‘Major’. Big, bluff and moustached, and now retired, who didn’t get up till 11.00 am, then proceeded to drink prodigious quantities of bitter for most of the day.

The ballroom was a tall-ceilinged, gaunt room with thick concrete walls, and cross beams. It echoed when empty. John had had the ceiling painted dark olive green, and papered the walls in a green stripe, to make the place a bit less barn-like. There was a tiny bar in the far corner, away from the balcony, with its tip-up seats for a cinema, through which we used to have to struggle to get in and out of the projection room. This box-like room was directly above the downstairs public bar, and it was Alistair’s proud domain, as part-time projectionist.

It was getting to the height of the season, and John had booked ‘The Good, the Bad and the Ugly’ to be shown that Monday. I was on the gate, selling tickets to whole families of visitors, young and old, groups of noisy, pushing youths and giggling girls, until we had sold every ticket and filled the place. The box of films had been marked ‘Reels 1, 2 and 3’, and this had already been picked up that morning by Alistair, and he had run the first bit of reel no.1 through to check the sound, lead-in and focus, and as the lights were switched off and the stragglers moved away from the now dark bar, the film began.

During the interval, at the end of the second reel, I went to the less crowded public bar for a beer. Coming back I met Alistair who seemed a bit preoccupied.

“What’s up?”

“Have you seen John?”

“No, maybe he’s in the kitchen.”

Alistair disappeared in search. The cinema audience settled down to the next half, and I took my seat in the balcony, blissfully unaware of the disaster which was slowly, but ever more quickly unwinding itself. After a further hour’s running time, the projection door opened, and Alistair came out, struggling over the legs of those in the balcony, and stopped when he got to me. His face was thunderstruck, numb with shock and misery. He had sat there in the projection box, watching horrified as the third, and apparently concluding reel was slowly going through the projector.

“What’s the matter?” I hissed.

“There’s no more bloody film left.”

“What do you mean, we got the three reels as usual.”

“Aye, but I've seen it before, and it's nowhere near the end. There’s about five minutes left on this reel and that’s our lot!”

“Your lot, you mean. Look at the place crammed full – they’ll kill you!”

“You’ll just have to go down and apologize.”

“I’ll no do that, och no, not me”, he moaned, his accent getting thicker the nearer he wished he was to Scotland and out of here altogether, to awake and find it was nothing but a terrible nightmare.

“Find John - get him to tell them.”

“I dinna know where he is”, he hissed. He would have wailed, but kept his voice low. No sooner had he finished speaking than the last frame of the last reel went clacking through the projector, with the usual scratches and blobs showing on the screen, and then a ghastly white square of blinding light appeared. Alistair clambered back to the projection room amid cries of ‘Boo’ and a few cat calls, and promptly locked himself in.

I saw John turn round. He was on the ground floor and I hurried down. People were becoming restless, and those near us even more so when they overheard me tell him the dreadful tale, he twisting round in his seat and squinting desperately through slit eyes at the projection box, now silent and dark. He stood up, a mixture of cold wrath, cold sweat, topped overall by a fixed, icy grin.

“Ladies and Gentlemen.” Catcalls and loud hisses – “as you are by now aware, we have run out of film. There are normally only three reels per film; these we have shown you... unfortunately the others must still be at Guernsey airport.”

A stunned silence followed, then swiftly followed by a rising tide of angry muttering and scraping of chairs. I was sitting with my back to the door, ready to bolt for it. “Good grief, this is it,” I thought. Some of the local heavies had got to their feet and were not waiting for further explanations.

“Andrew will issue you with free tickets for a complete showing on Wednesday, or give you your money back.”

“Oh yes, will he?” I thought. I was already spotted by the first of the angry crowd. I turned, left, and got quickly into the little box office, locking the door behind me. “Everybody’s locking themselves in”, I thought. The comments ranged from the merely abusive to the downright tearful. “We can't come back – we’re

sailing tomorrow”. A refund for them then.

“Couldn’t run a piss-up in a brewery.”

“Me and some of the lads will have to sort you out.”

This went on for what seemed an age - perhaps ten minutes or so. When the last of them had gone, I locked up with shaking hands and went to the bar where I found Alistair and John staring fixedly, mournfully, into their glasses. I bought myself a Scotch.

I said “What a bloody disaster.”

“Och, don’t go on about it.”

“Well, perhaps one will learn to check the total reels in future”, said John.

Having fared the worst of all, I reflected glumly and without hope that Alistair would get his comeuppance, but was unaware quite how soon, and in what an embarrassing way this would happen.

Alistair was in the habit of drinking a few cans of McEwan’s while showing the films. The projection room was tiny, and directly above the public bar. Access was very difficult, across the legs of the cinema-goers in the balcony, so any quick trip to the loo was out of the question. Hence the large can, an empty cherry pie filling can - catering size. Alistair was lazy about emptying it.

“Och, the evaporation does the trick”, he once explained, when I asked him about the sordid can on the floor. It was another film night, and during the interval, I went down to the public bar. I got my drink, and noticed old Jack, the owner of Brigg’s Hotel, saying to one of the locals: "Oh yes,” pointing to a gentle amber coloured stream dribbling down between the ceiling and a supporting beam, into the bar, “it’s one of the pipes leaking. I can even tell by the colour!”

Alistair was in the bar and sidled up to me with his eyes avoiding everyone’s in case his dreadfully guilty look gave him away.

“Och, let’s get out of here”, he said, scarpering for the door.

“What happened?” I asked, once outside. “I backed into the soddin’ thing when I was changing reels, and knocked the bloody thing over. Full it was too!”

“Serves you right!” I said, trying to keep the glee out of my voice, and my face straight. I did a bad job. He never did use that can again.

CHAPTER TWO: STEPHANIE AND THE CRABS

“Pierre de who?” I asked, incredulous.

“Pierre de Prince”, replied John, stressing the last name, in French.

“What does he do?”

“He’s to help you in the season, and to play the piano before the films begin, and during the intervals.”

“Heck!” thought Alistair and myself.

“He looks like a small version of James Coburn, but twice as pretty, when he wears his D.J. and a frilly shirt,” said the barman, who knew him. “Mauve”, he added.

“Mauve what?” I asked.

“Frilly shirt”, said the barman.

“Yes, but it’s the grey curls”, said Alistair, who had seen him. “And the gold earring.” Hmmm.

Dinner service and in comes Pierre (Pete), by then, plastered. With an open bottle of Guiness stuffed under his belt. He pulled the Guiness out and had a swig, and made his way towards the dining room. We both tried to stop him, but too late - when we got to him, he was doing his ‘O.K. Corral’ routine hiding behind the service desk, down on one knee, one eye shut, darting from behind the desk, shooting the diners, who were his deadly targets. One or two of them looked up, surprised; others, thankfully, hadn’t noticed.

There was enough noise and comings and goings for him to be largely missed... but not for long... We got him quickly into the kitchen and tried to sit him down and get black coffee down him. We shouldn’t have bothered, just sent him to his room to sleep it off.

We had just managed to get him settled and out of the way, in the stillroom (the boss hadn’t spotted him, thank goodness), and were able to continue serving, when we were horrified to see him in the dining room doorway with a silver ‘flat’ in one hand, with the beef on it for four people, and a serving spoon and fork in the other, with a grim, set look on his face, all ready to take the Major his dinner. Despite full hands, I still just managed to scoop the flat from his manic grasp. “Thanks Pete, I'll serve the Major.”

He eventually left, hiccupping morosely, swaying and taking pulls at the nearly empty bottle, wistfully humming a snatch of tune from ‘My Fair Lady’, that week’s film.

***

Stephanie was magic. Ratbag was her affectionate nickname. All of eighteen, and tiny, she was to be waitress for the season, Pete having been relieved (thankfully) from that duty. She was on vac from a London Polytechnic, where she was doing some sort of ‘art thing’ we were never quite sure what, and it didn't really matter.

It was John’s normal practice to give the residents a cold supper for Sunday night, and since we were on an island, it seemed natural to give them crab, freshly caught and cooked. There were French windows leading from the dining room onto a small courtyard with a tiny fish pond, plus fountain, all ready to become the scene of another disaster.

Unknown to Stephanie, Alistair and I hi-jacked a huge basket of live crabs from the back of the kitchen (the ones destined for the following day’s supper), and emptied it in the courtyard, where the crabs started, naturally enough, wandering around, waving huge claws, and opening and shutting them menacingly. We waited until Stephanie had just finished serving a diner in the packed dining room, then pulled her out into the dimly-lit patio, turned, shut the French windows and locked the door. She couldn’t see what we had done at first; just standing there with a bemused and slightly annoyed look on her face, her hands on her hips. Any trouble she was expecting she wasn’t expecting at ankle level. One of the gigantic crabs moved onto her foot. She looked down, saw this monster with its endless number of legs, shiny dark shell, eyes on stalks, claws the size of a child’s hand, waving near her ankle. She screamed and screamed and screamed, seeing the other dozen or so crabs moving in her direction. We let her in as quickly as possible, for two reasons; the screams were from the soul, she was terrified, and we didn't want to alarm the guests. One or two were frozen in a posture with a spoon or fork halfway to their open mouths, others were merely inquisitive about the shrieking.

“Tomorrow night’s supper”, I explained in a loud voice to the dining room in general, and then I turned and started dealing with them. The wretched things had really woken up by now, and what with her yelling like that, frightening them silly, they were scuttling off in all directions into the undergrowth. Alistair managed to find a torch while I got the basket. “Here's one... and another.” “Get that one over there, quick!”

“This was all your stupid idea”, I said. “Aye, but you went along with it for the crack”, replied Alistair.

“Quick – let’s get the rest before John finds out they’ve gone walkabout.”

At last we had collected all (we thought so anyway) of those angry and frightened crabs, which had desperately tried and failed in their last ditch attempt at freedom. Talk about the Great Escape!

We went back inside to find a quieter but still fuming Stephanie, who soon saw the funny side. “Rotten sods”, she said, kicking Alistair in the shin. “And as for you Andrew...” I made myself scarce.

***

Pierre's sexual preferences were under discussion, and the general consensus of opinion was that we didn’t know, but none of us had ever seen him with a woman, and if anything, he was probably queer. How wrong can you be? The largest hotel on the island had staff chalets with paper-thin walls, which afforded no privacy at all to the occupants. One of the Portuguese chambermaids told the story of how, when she was trying to sleep, was kept awake by the noises from the adjoining room, occupied by one of the waitresses. The chambermaid found out next day that the gentleman in question was none other than Pierre. “I cannot sleep,” wailed Maria, “all night long she is going ooh-ooh-ooh, and he roarink lika da bool!”

CHAPTER THREE: DURBAN AND WORSE

I had always wanted to go and live and work in South Africa - then still a land of promise, gold, diamonds, vineyards and white sandy beaches, Xhosa, Zulu, Indian; Table Mountain, Kruger National Park, the Bush, with giraffe, wildebeest, lion, hippopotamus, and endless sunshine. I applied for a permanent residence permit, for I genuinely wanted (at that time), to go and live there for the rest of my life. After much form-filling, I got the permit delivered to me, together with an air ticket to get me to Johannesburg at the South African Government’s expense.

I gave in my notice at work (by now I had returned to damp England), and was really twitching to be off.

The flight from Heathrow was smooth and uneventful, taking about ten hours to get to Salisbury, Rhodesia, because in those days South African Airways were forbidden to fly over several black-governed countries, and so had to go around the western bulge of Africa, refuelling in the Canaries. A brief stop at Salisbury, then on to Johannesburg, where I was summarily told to “Git in the right queue, min” by an Afrikaner official. A taxi ride took me to the hot, high-rise centre of the city, and I was put down at a smart hotel, to stay the night, before my flight to Durban next day.

Durban was hot and humid, the beach was grey, and the sea looked uninviting. There were lots of tall apartment blocks, hotels with seafront verandahs, palm trees, an aquarium, Zulu rickshaw pullers in fantastic head-dresses, with lots of traffic, all driving on the left, Indians, Africans and Whites all jostling on the crowded pavements.

The hotel where I was to be an Assistant Manager was in Smith Street, and I looked balefully at the ten storey, two-star hotel. Over three hundred and fifty rooms, but it was difficult to tell exactly how many there were at any given time, because so many were out of commission for repair or redecoration. The general manager was a bluff Englishman with ginger hair and freckles, called Mills, and our dislike of each other was instant and mutual. There was only one assistant manager until my arrival; how they managed to keep the place running with only one manager and one assistant, I didn’t dare ask. My hours were from 5.00am, when I had to kick all the African room-boys out of their quarters, then right through till after lunch, when I had a short break until 6.00pm, then another 8 hours until 2.00am, when the nightclub closed. I was so tired at the end of the day that I felt thin and almost transparent, my eyes were playing tricks, and the scene in front of me would start fluttering at the edges.

On my day off, I stayed in bed till lunchtime, then I’d saunter to a bar on the seafront, and drink ice-cold Lion Ale. I’d do whatever shopping I needed, then out to a small restaurant for a steak and half a bottle of the best Cape Claret, and very good both were too.

Since we were still officially in Winter, it was thought necessary for me to get a morning suit made. The best place for this was in the Indian Market, in Cathedral Road, for here were the best tailors’ shops. I was duly measured up, and after a week and one fitting, I had to part with £60.00, which was a lot of money in 1972, even if it was for a very well-made and well-fitting suit.

Why we needed them for a two-star hotel, goodness knows. Perhaps they were trying to impress the punters, but it was a bit over the top.

A few weeks after this, Summer was officially declared by the Manager, and we had to wear white Safari suits in the morning and afternoon, then dinner jackets after 6.00pm. A Safari suit consisted of a white cotton pair of long trousers, with a loose jacket top, also in white cotton. What with the white socks, and white shoes, I looked like a cross between the big white hunter and a seedy extra from a Bogart movie.

We had a new assistant who started a few weeks after I did. He was a slow-moving, finely featured, up-market German called Kroll. He smoked their cigars and wore a grey pin-stripe suit - no safari gear for him! He was alright to work with, but he got right up the manager’s nose, as they were poles apart in looks, nationality and character. Mills was gunning to get shot of him. We were not allowed to drink or smoke on duty, and it was a long and very hot night, when we were cashing up the huge dispense bar which served the ballroom. I made the fatal mistake of joining Kroll in an ice-cold bottle of lager. Of course, who should walk in but Mills. He gave me a withering look, and told Kroll he wanted to see him in his office.

Next morning, when on my rounds of the kitchens, I found Mills having his breakfast. Kroll I hadn’t seen.

“I’m sorry I blew it for you”, I said unhappily.

“The one chance of getting rid of him I could have used…” he said.

“I know, it won’t happen again.”

“It better bloody not, or you know what will happen.”

Kroll was in our shared office when I got back downstairs. “That bastard tried to nail me last night, but thanks to you, I'm still here”, he said, with a touch of venom in his voice.

“You don’t like it here, why don’t you find another job?”

“I’m trying, but I’ve had no luck yet.”

He left without a word about a week later.

***

There was a first-floor bar and swimming pool which was a popular venue, the hotel catering mainly to young Afrikaners on holiday. One evening, some non-resident lads (lads - ha! they were all over six feet tall and built like brick-built khazis), came running down the main foyer steps all soaking wet. They had been throwing each other into the pool, fully clothed. I was surrounded by them, and was dwarfed. They were a bit drunk, but no trouble, all being in a party mood. It was just then that half a dozen of our resident Afrikaners came through the swing doors. They thought from what they could see, that I must be having some sort of trouble with the dripping crowd. I assured them I wasn’t, and that they were just leaving, until one came running back and aimed a hefty kick at the backside of one of the residents. The others all came back quick as a flash and within seconds the foyer floor was covered in swearing, punching, writhing ‘yapies’. The hall porter stood well back and called the police. As soon as the word ‘police’ was heard, the swimmers all melted out of the door like quicksilver. One of our residents had a cut lip, one had lost a bit of tooth and another had a nasty red bulge on his cheekbone. Nothing too serious and they were solicitous about my welfare. I couldn’t condone what they had done, but was grateful for their concern.

Eventually my hours eased somewhat - twelve on, twelve off. One night I had just crawled into bed at 3.00am, when the ’phone went.

“Head night porter here, sah.”

“Yes, what is it?”

“I cannot say, but come quick, come quick, sah!”

Why he couldn’t tell me over the ’phone, I don’t know. They never would. I think they liked to see me jump when they ’phoned, and nothing less than my person would satisfy them. I pulled on a mac over my underpants, found a pair of shoes, and slopped downstairs to the foyer. There, pacing up and down was an irate gentleman, aged about fifty or so.

“Good morning, what can I do for you?” I asked warily.

“My daughter is in this hotel, she left home with her boyfriend, and she’s under age.”

He gave me her name, which I checked against the register, and sure enough, there was someone of that name in room 208.

“Wait here, I’ll give her a ring.”

No reply. “I’ll go and see if she’s in, sir”, I said, fumbling for my pass-keys.

“I’m bloody well coming with you,” he said twitching. “If she’s there and won’t leave, I’ll call the police.”

We went upstairs, found the room, knocked. No reply. I knocked again, then used my key to get in. The room was in a hell of a mess, the lights were still on, bathroom empty. Our bird had flown, with boyfriend, into the sweaty Durban night.

“I’m sorry, she must have left, and in a bit of a hurry, too.” She must have sneaked out through the underground garage when the night-porter wasn’t looking, for she had not paid her bill either.

“I’m sorry, sir, there’s nothing more I can do, but if she turns up again I’ll let you know. Please give me your phone number, and address.” This he did and, thankfully, he left. I staggered off, numb, to try and find oblivion in sleep.

***

There was a bar for the Indian workers, and one could be forgiven for thinking one had walked into a public lavatory. Red tiled floor, once-painted walls, now peeling, two florescent strip lights overhead, a battered old wooden bar top, and till which never had any float, to discourage thieving... The Indians were the only ones allowed in, and they mostly frequented the place between finishing work and catching the last dirty bus home. They had little time, most of them, so used to drink the most effective mixtures, to have the desired effect as quickly as possible. One such mixture was a large neat cane spirit followed by a double Cape port.

When it was time to close the bar, two of us assistant managers would go and count the take, and check it against the till roll, check food stocks against cash taken. Chilli Bites was a very popular snack, apart from the usual peanuts and biltong. An armed guard was always there to meet us, and we had to decide which of the three exits we could use, according go how many drinkers there were in there, where they were seated or lolling, and what the general mood of the customers was. We had to scarper sharpish once, and made good our escape with the takings, by using a door which came out behind the dance hall's stage. We then had to negotiate the band (deafening), who were playing ‘On a Clear Day you can see Forever’ (badly), taking care not to trip up in all the cables which snaked over the stage, then we had to force our way through the heaving sweaty mob of whites to get to our office.

The whole messy, tiring, and unpleasant job was getting me down, so I started writing to, and phoning several possible employers, and despite seeing several, I was unable to get further work in Durban, so I decided to try my luck in Cape Town, which I was told was a much nicer place to be anyway.

The night before leaving, I got into a card school, and was doing fairly well, so we kept on drinking Lion Ale and playing poker until five in the morning. By this time the sun was well and truly up, although none of us had seen it, because we were sat in the blacked-out club. I went for a swim, the only time I did so during my whole stay in Durban. The water was grey, so was the beach. The sea was warm enough, it should have been, it was the Indian Ocean after all.

My plane was due to leave at six that evening, so I decided to crash for a few hours. No sooner had I got into a deep sleep, than there was a hammering at my door. I struggled out of bed, on with the mac, and answered.

“Police.” He flashed his warrant card at me. I didn’t have time to

read it. “What's this about?” I asked, noticing the General Manager was trying to get into the room as well. As a witness, I suppose.

“Are you leaving this hotel today to travel to Cape Town?”

“Yes”, I said.

“We must search your belongings now.”

“Help yourself”, I said giving Mills a quizzical look. He just looked bleakly back, and sat on the bed.

Another policeman came in, younger, in uniform, and I was feeling like death warmed up. Every record sleeve was checked, my bank pass book and statements gone through, to check for any deposits substantially larger than my salary could account for. Nothing.

All my packed clothes, books, and belongings were thoroughly rifled and put to one side. After an hour of searching they found nothing, and left. I was later told by one of the receptionists that the CID had eventually caught the junior porter red-handed using his pass-keys to get into a room to try and steal some jewellery. An Apocryphal end to the whole sorry story was that the boy was sentenced to be birched, but how true that was, one couldn’t be certain.

CHAPTER FOUR: CAPE TOWN AND ONWARDS

An uneventful flight got me down to Cape Town in good time, and I checked into a pretentious little 2-star hotel in Sea Point. I moved out the next morning, and found a small, pleasant 4-star hotel, with a superb backdrop from the car park. Table Mountain soaring some 2,000 feet into the deep blue sky, topped, on some days, with the ‘Tablecloth’, which is just what it looked like. Caused by warm, wet air being forced up several hundred feet, cooling and contracting to dew point, and so forming a thick ‘cloud’ which covered the top of the mountain, spilled over, and as it descended into the warmer air, dispersed like steam, and the rest of the escarpment was in brilliant sunshine again. Beautiful.

I asked the Assistant Manager if there was any work to be had in the hotel, and next day was offered the job of re-opening the downstairs ‘cocktail bar’ which had been shut due to lack of suitable staff to run it. I was introduced to Jim, an expatriate

Englishman, who smoked the vilest cigarettes called ‘Gold Dollar’ (only smoked by the Blacks). His comment was: “Fifty million Africans and one white man can’t be wrong!”

I was given a bar-boy to help clear up the mess left, and to strip all the shelves, ready for stock-take and restocking. Later on in the morning Jim came down to Sykes-test some of the bottles of spirits to see that they were all right for strength. The first two were almost 50% water, and so we had to test all the bottles, only to find that they had all been watered.

“Well strike me, the little bugger must have been making a fortune,” said Jim, “I’m surprised that no-one complained to the boss about it.”

“What do we do with this lot, then?” I asked.

“We’ll have to show it to the old man, and then ditch it after we’ve written it out of stock.”

“I’ll have to re-order all the stuff that was duff - what sort of levels do you keep the cane at?” I asked (Cane was a spirit distilled from cane sugar, but not tasting anything like rum, rather more like vodka, but lethal).

“We sell a lot of it, so keep a balance of six at all times, and the same for the more popular local brandies.”

Wines, sherries, brandies, ports and cane are all made in South Africa, and some of the quality was excellent, though a few of the rougher brandies needed avoiding.

The hotel manager let me stay in a guest room until I found myself a flat, and so I went to a real estate agent down-town, and they came up with a small flat which suited me fine. It was just a five minute walk from work, in Orange Street, a pleasant road running from the top of Adderley Street in the city proper, to de Waal drive, with Table Mountain beyond.

The bar was quite modern, with black upholstered seats and stools, and large black and white photographs on the walls, showing scenes of the Houses of Parliament, and the Heerengracht, the wide boulevard running down to the sea, with the statue of the founder, or rather discoverer of South Africa, Jan van Riebeeck, towards the seaward end. These photos were lit by discreet spotlights, and the effect was fairly formal, but intimate.

We had the idea of trying to pull in more trade by setting up a ‘soup-and-cheese table’ lunch for businessmen, and what with the variety of cheeses, pickles, French bread, etc., the numbers steadily increased, and we gained a few regulars, which boosted everyone’s morale.

For the evening session, just after I opened at 5.00pm, I used to get a couple of copies of the Cape Argus (the evening paper), and have nuts, olives, etc. on the bar, with some soothing music on tape, which helped smooth out some of the wrinkles from the businessmen after a long day at the office, before they went home to their wives. The hotel was on one of the main roads going north out of town, and anyone going either east or north-east would normally use this road. So we started to pick up quite a crowd early on.

There was an upstairs bar which served the Grill Room, and it was here that two crazy ex-pats worked. One was Danny, an Irishman who had been working in the bar at Jersey Airport, and Jan, a tall, fair-haired Dutchman with a beard, and lopsided, toothy grin, due to his false teeth.

I bought an old Volvo from a rogue called Harald ‘Harry’ Laski, an ex-skipper. He had a small restaurant near where I lived, and I used to eat steak there most nights. One could sit at the bar and eat while watching him work the grill area, cigar stub in mouth, or sit at one of the several pine tables. The steaks were thick, prime cuts, beautifully grilled, the sole were fresh, and, although he didn’t have a licence, you were always welcome to bring your own wine. Once he got to know that you weren’t a copper’s nark, but a regular, he would keep a few bottles of your favourite stuff under the counter. One day, I went in and he wasn't there. I asked his wife where he was.

“Still at police headquarters,” she said apprehensively. “What’s he been up to?” I asked.

“He’s been charged with I.D.B.”

“What’s that?”

“Illicit Diamond Broking,” she said, “I always knew the silly bastard would get caught one day. Goodness knows what will happen; at best a fine and a suspended sentence, at worst...” her voice trailed off.

“Come on love, cheer up. When will you know the worst?”

“Tomorrow morning, after he’s gone before the Magistrate.”

“Will they let him out on bail?”

“Hopefully, and then we’ll know what his lawyer thinks he can get away with.”

“O.K., while we’re waiting, could you do me a sirloin, rare, and pour us both a drink? You look like you need one.”

As it happened, he got a three year sentence, suspended for five years, with a fine of ten thousand rand, which was quite a lot of cash in those days.

After several months at the hotel I was starting to get itchy feet and so I started to look for a new job. I scoured the Argus, and saw an advertisement for relief managers to work for a small chain of drive-in diners. I applied for an interview, and the Assistant Director of Operations came over to the hotel and we had an informal chat about the job, my qualifications and the pay, and he said he would let me know in a couple of days.

I got the job, handed in my notice, and went out on the town, getting home very late, and parked my car on a single yellow line, which was all very well until 8.00am next morning. I had to report to Goodwood branch for my first day’s work at ten in the morning. I awoke at nine, feeling like death, head thumping, the walls wouldn’t stay still long enough, and my tongue stuck to the roof of my mouth. I struggled into my clothes, ran downstairs, round the corner, praying and praying all the while that I would be missed by the traffic cops. As I flew around, the corner I was just in time to see the front end of my car being raised up by a tow-truck’s crane. I ran to the driver’s side and pleaded:

“Can’t you put it down again, go on, nobody saw you.”

“Not once I’ve hooked her up, I can’t.” “Where’s the car pound then?" When he told me my heart sank. It was right the other side of Cape Town, in a suburb.

I hailed a taxi and followed, miserable, all the way to the police pound. I rang my new boss to explain what had happened, and that I was going to be very late. It was nearly ten by this time.

After cursing, sweating and spitting blood for at least half an hour, it was my turn to go to the window and claim back my car. After paying the taxi, the fine and a ‘tow charge’ (Ha!), I was nearly broke. I went out to try and find her and when eventually I climbed in and tried to start her, the battery was flat. I could have cried.

Instead I just managed to walk her backwards on the starter motor to block the exit road. Then I waited till I saw two traffic cops, called them over and told them I needed a push. It was a very hot, dusty day, and the car took several goes before she fired. The two breathless and red-faced cops just got a wave of my hand out of the window as I roared off thinking that at last there was some justice in the world.

***

My new boss was a tall, crew-cut, Afrikaner, with a comic-strip square jaw, peering eyes and thick lips. He was a part-time policeman, and ruled the drive-in with a rod of iron. I was shown the books, money and stock, all worked out on a simple system, but which involved doing a complete food stock check - every bun, sausage and burger every night. Anything over or under was recorded, and balanced daily. Jan, the boss, was normally cheerful with me and the customers, verging sometimes on the bluff, and thank goodness he could speak Afrikaans - my knowledge was rudimentary, and I could only just get by with the little bit of Dutch that I had picked up during holidays in Holland. Most of our staff were Cape Coloureds, not native Zulu or Xhosa, and we had to watch them like hawks; they really liked to drink cane or port in vast quantities, and then fail to turn up for work at all, or try to bring booze onto the premises with them. If they lost one of their sequentially-numbered dockets, they had to pay a fine of ten rand, which was about half a week’s wages.

Unhappily, I only had to do this once to a coloured, who was also a lay preacher in his local Church, the most unlikely person to try thieving, especially in such an easily discovered manner, for all docket books were issued, signed for and checked at the end of each shift. It made me unhappy to have to do it, and he saw this, and started pleading, which only made my task harder.

Once I had been suitably trained up in the ways of the Company, I was let loose on three branches as a relief manager, doing days at each to give the other managers time off. One of the branches was in Groot Constantia, right in the heart of the wine-growing area of the Southern Cape. The beauty of the surrounding country with its well-tended vines, and beautifully maintained elegant Cape Dutch houses was memorable. Another of my branches was not in such a pretty place. It was right on the edge of the notorious no-go area called ‘District Six’. I was advised never to drive through there, because if I had a breakdown, both myself and the car stood in danger of being taken apart.

The first time I tried the run, I could see why. The area was partly demolished, with a view to flattening the whole area, re-settling the ‘Skollies’ well out of Cape Town, and rebuilding it all as a high-class white residential area. There were crumbling blocks, dirty streets, naked light bulbs, torn posters, disheartened coloureds, lounging against walls, or in small sharp-eyed groups, hanging around on the corners. The only reason why I bothered to run the gauntlet like this was because the distance between my flat and place of work was quartered by taking this route, and I calmed my worst fears by telling myself that it was a downhill run, and if I broke down, I could always roll the car all the way downhill to the bottom. Luckily nothing ever happened to the car, but each time I came out into the more salubrious surroundings of Eastern Boulevard, I uncrossed my fingers.

One night, after finishing well after midnight, I was waiting for the staff minibus to come and pick up the six late shift staff. We waited until one in the morning, and then I decided to give them a lift to their township of Bontheuvel. We all piled into my none too large motor, and I was given directions as to how to get there. The streets got meaner, the street lights with working bulbs fewer and fewer. The houses were all prefabs, made from asbestos, all single-storied. Goodness knows how many families lived in each. Weeds grew in the cracks in the pavement, and in the road, and each street just had a number for easy identification by the security forces. The Coloureds all piled out, some to one street, some to another. At last it was my pleasant job to get back to the well-lit main highway into town, and to shut the door of my flat behind me, thinking how lucky I was.

CHAPTER FIVE: ONWARDS TO OZ

I wrote a letter to my cousin Mark, living in Australia, whom I hadn’t seen for 20 years. He had a sheep farm some 200 miles south of Perth, and as I had had enough of South Africa, since I was rapidly becoming aware that I was at the end of my tether there, I was determined to try Australia.

His reply some two weeks later was most encouraging: along the lines of “Great to hear from you. When can you come over?”

I met Michelle, my current girlfriend, in the Grill Bar of the hotel where I used to work, and explained my plans. She, being a well- travelled lady, although a bit put out at first, agreed that I ought to take the opportunity, and go to Australia.

“When would you go?” she asked.

“In about three or four week’s time. I have to sell my car to pay for the sea passage.”

“What’s wrong with flying?”

“Nothing, except I can’t afford it.”

“So - how long does the sea voyage take?”

“Ten days, and the only ones to do the run now are the Italian line, Lloyd Triestino.”

“Well, at least you’ll get your fill of pasta”, she smiled.

“And Stock Brandy, too,” I reminded her.

I went to see Harry at his restaurant. “Harry, I haven’t got the bill of sale for the car you sold me, and I’m advertising her for sale today”, I said.

"Klein problem, just go to the motor-bike showroom down-town, you know where it is, and I will tell Jacob to have the papers ready for you this afternoon.”

“Thanks, get us a beer, would you?”

Up came two half-litre bottles of ice-cold Lion Ale. “Here’s to Australia, Cheers!” said Harry.

Two days later I got a message giving me a time and a place to meet a possible buyer for the car. By now I had got all the papers in order, and drove to Orange Street, where I was met by a large Lincoln full of Coloureds.

“Just step inside here while Jannie here takes your motor for a little test run,” said a toothless guy. I handed Jannie the keys, there seemed little else I could do. I was in the back of a crowded car, sweating gently, waiting, waiting.

Nobody said a word. It was like one of those moments in gangster movies, when you knew someone was going to get theirs, and it was usually the guy in the back seat, surrounded by heavies. My guts were turning to water. What if the car doesn’t come back in five minutes? Would they take off, dump me on the N2 Highway, left to walk home, without a car, and no cash? While all these, and worse, thoughts were passing through my mind, my little orange Volvo came screaming round the corner.

It pulled to a stop, the driver switched off, got out, and sauntered over. There followed a rapid exchange in pidgin Afrikaans, of which I could understand nothing. The one in charge sat at the wheel of the Lincoln, told the one on the right to pay me the money I had asked for in the advertisement. No bargaining, no quibbling.

Out came the thick, greasy bundle of large denomination notes. I handed over the papers, which they checked, and then they let me out of their car. Both cars roared off, leaving me with a dazed feeling, a bundle of notes in my hand, and a terrific thirst. I put the money in the safe at the hotel, had a beer and then booked a farewell dinner for myself, Michelle, Danny, Jan and another couple, at a Greek restaurant at Sea Point, for a week ahead.

That evening I went for dinner at Harry’s restaurant, and in a quiet moment, he took the opportunity to go over to one of the tables, and started talking to a man sat there. From out of his top pocket he pulled a handkerchief, opened it on the table, and there, for the first time in my life, I saw raw diamonds. About half a dozen of them, each the size of a fingernail. Dull, frosty-looking, and dangerous. “Hell!” I thought, he’s been busted already, and he has a suspended sentence hanging over his head like the sword of Damocles. I turned quickly back to my steak, pretending I hadn’t seen anything.

Better not to know, if questions were going to be asked.

***

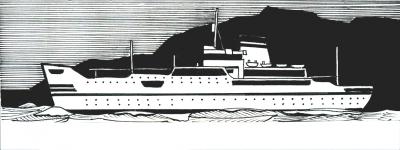

The evening of my departure I took a taxi to the docks, and there she was, the Galileo Galilei, a fairly old-fashioned but elegant looking liner, which was going to take me across the Indian Ocean, ten days at sea in the middle of the Southern Hemisphere’s Winter. All I had in the way of luggage was my frame pack, with bivouac, bedroll, and bare necessities. All the rest of my things I had had shipped back to England from Durban.

There was confusion everywhere. Black porters, white customs officials, an American whose papers were not in order. The corridors on board were a cross between ‘British bulldogs’ and the rush-hour on the Northern Line. Found my cabin at last. Two decks below sea-level. It was basic, but clean and comfortable. I dumped my pack, and took the same taxi, which had been waiting for me, meter running of course, back to the hotel, where I had to drop off a book that I had borrowed, organize Danny to pick me up from Michelle’s in half an hour (we were due to sail at 7.30pm and it was already 6.15pm), to take me back down to the ship. I was walking briskly down Orange Street towards Michelle’s mother’s flat, when I saw a dark-skinned guy in a foreign sailor’s uniform pushing a broken-down Austin. He flagged me down, speaking in broken English. I tried to see if I could help fix the car, but with his broken English, and my total ignorance of Iranian (for that was his nationality), it proved a bit of a stumbling block.

We settled for the nearest garage, a few hundred yards away. By the time I got to Michelle’s, I was hot, sticky, late, and my hands were covered in oil and dirt. A quick wash with Vim, a swift gin, and Danny was already tooting outside. I said my farewells to Michelle’s mother, and we piled into Danny’s 2.8 Jag, which was crowded with Joan, his wife, and Jan and ourselves.

We arrived just in time to see the tourist class gang-plank being craned off the ship, so we raced to the first class end of the ship, and Michelle and I said our goodbyes.

Soon a shrill whistle blew and they started to haul that one away; so I quickly ran up it and leaned on the railing nodding, smiling, straining to hear what was being said from so far below. By this time I was dying to go to the loo, but didn’t know where to begin looking, and I daren’t move in case the ship sailed, and I wasn’t there to wave back to the little party huddled on the now chilly quayside. After a further twenty minutes a final line was cast off, and with a belly-quivering blast, the ship’s siren sounded a long, mournful note over the windswept city, and over us all. She turned, put her bows out to the open sea, and I waved and waved until I could see my friends no more. Soon even the brightly lit main streets were just an orange blur on the skyline, and we rounded the Cape and the bows dipped into the whitecaps like a long nose into beer froth; and we headed out into the darkness that was the Indian Ocean.

***

The complete book - 16 chapters, 100 pages - can be purchased in paperback at Lulu:

http://www.lulu.com/content/1087505

Thanks for reading :-)

Created 2007-12-27 21:28:38 by strix and filed under things

Add Comment

Subscribe to this blog by RSS. Subscribe to this blog by RSS.

|

|

|

|